When someone with Parkinson’s disease gets nauseous, it’s not just a stomach issue-it’s a medical tightrope. The very drugs meant to help with nausea can make the core symptoms of Parkinson’s worse. This happens because many antiemetics work by blocking dopamine receptors, and Parkinson’s is a disease where dopamine is already running dangerously low. The clash between treating nausea and protecting movement isn’t just theoretical-it’s a real, daily risk for thousands of patients.

Why Dopamine Matters in Parkinson’s

Parkinson’s disease slowly kills off the brain cells that make dopamine, a chemical messenger crucial for smooth, controlled movement. Without enough dopamine, people experience tremors, stiffness, slowness, and balance problems. The main treatment, levodopa (often paired with carbidopa), tries to replace what’s lost. But it’s a balancing act. Too little, and symptoms return. Too much, and you get uncontrolled movements. Now add an antiemetic that blocks dopamine receptors, and you’re essentially turning down the volume on the very system you’re trying to support.The Problem with Common Antiemetics

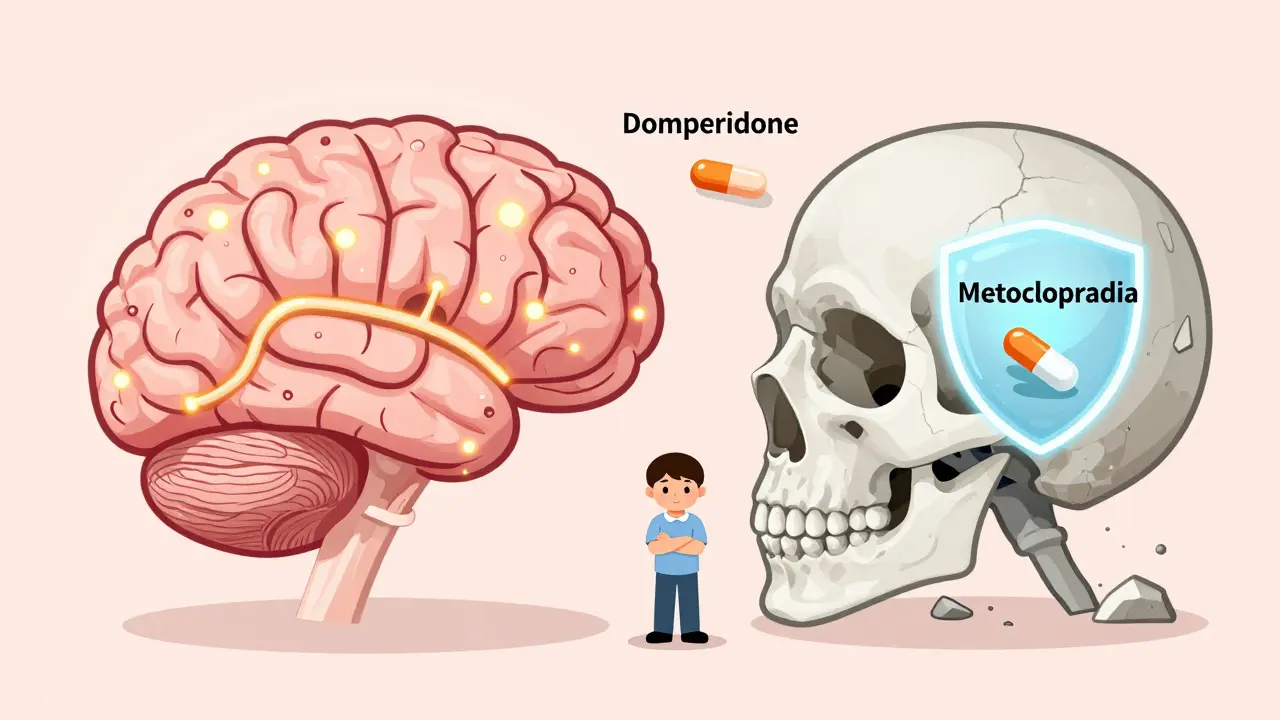

Many antiemetics you’ve heard of-like metoclopramide (Reglan), prochlorperazine (Stemetil), and haloperidol (Haldol)-are dopamine D2 receptor blockers. They work great for nausea because they calm the brain’s vomiting center. But here’s the catch: they don’t know where to stop. If they cross the blood-brain barrier, they start blocking dopamine in the basal ganglia-the same area already starving for dopamine in Parkinson’s patients.Metoclopramide, one of the most commonly prescribed, has a 95% risk of worsening Parkinson’s symptoms according to the American Parkinson Disease Association. It’s not rare to hear stories like this: a patient gets metoclopramide in the ER after dental surgery, and within hours, their tremors spike, their walking freezes, and they can’t get back to baseline for weeks-even after increasing their levodopa dose. A 2022 survey from the Michael J. Fox Foundation found that 68% of Parkinson’s patients who received these drugs in hospitals reported a major worsening of movement.

Even more alarming: a 2022 study in the Journal of Parkinson’s Disease found that only 37% of emergency room doctors knew metoclopramide was dangerous for Parkinson’s patients. That means nearly two out of three ER physicians are prescribing a drug that could send someone into a severe “off” period-just because they weren’t trained to look for the risk.

Domperidone: The Safer Alternative

Not all dopamine blockers are created equal. Domperidone (Motilium) works almost entirely outside the brain. Thanks to a natural defense mechanism called P-glycoprotein, it gets pushed back out of the bloodstream before it can enter the brain. That means it blocks nausea-causing dopamine receptors in the gut but leaves the brain’s dopamine alone.Studies show domperidone has less than a 2% risk of worsening Parkinson’s symptoms. In patient surveys, 85% reported it effectively controlled nausea without any drop in mobility. It’s the go-to choice in Europe and Canada. But in the U.S., it’s not FDA-approved for general use. The FDA only allows it through a special investigational drug program due to rare heart rhythm risks at high doses-risks that are minimal at the low doses used for nausea. Still, many neurologists will write off-label prescriptions for Parkinson’s patients who need it.

Other Safe Options

If domperidone isn’t available, there are other paths:- Cyclizine (Vertin): This drug blocks histamine receptors, not dopamine. Risk of worsening Parkinson’s? Only 5-10%. It’s often the first-line pick in UK guidelines.

- Ondansetron (Zofran): A serotonin blocker. Minimal dopamine effect. Risk around 15-20%. It’s good for chemo-like nausea but sometimes less effective for levodopa-induced nausea.

- Levomepromazine (Nozamine): A middle-ground option. It has some dopamine-blocking power, so risk is 30-40%. Only use it if nothing else works-and only after consulting both a neurologist and a palliative care specialist.

Dr. Alberto Espay, a Parkinson’s expert at the University of Cincinnati, says the most common medication mistake he sees is prescribing metoclopramide for nausea. He urges doctors to start with non-drug fixes first: ginger (1 gram daily), eating smaller meals more often, staying hydrated, and avoiding greasy or spicy foods. These simple steps help a surprising number of patients.

What to Do If You’re Already on a Risky Drug

If you or a loved one is currently taking metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, or a similar drug and has Parkinson’s, don’t stop suddenly. Talk to your neurologist. Abruptly stopping these drugs can cause withdrawal symptoms. But do ask: Is this the safest option? Is there a better alternative?One patient on Reddit, who goes by ParkinsonsWarrior87, switched from metoclopramide to cyclizine. “The difference was night and day,” they wrote. “No more freezing episodes that I’d been having weekly.”

How to Protect Yourself

The American Parkinson Disease Association has distributed over 250,000 wallet cards since 2018 listing medications to avoid. If you carry one, you’re 40% less likely to be given a dangerous drug. Here’s what to do:- Carry your APDA wallet card or a printed list of contraindicated drugs.

- Always tell every healthcare provider-ER staff, dentists, pharmacists-that you have Parkinson’s disease.

- Ask: “Is this antiemetic a dopamine blocker?” If yes, ask for an alternative.

- Insist on documentation: “Parkinson’s disease: verify antiemetic safety” should be written on the prescription.

- Know your safe options: cyclizine, domperidone (if accessible), ondansetron, or ginger.

The Bigger Picture

This isn’t just about one drug or one side effect. It’s about how medical systems fail people with complex conditions. Parkinson’s patients are often older, have multiple medications, and get treated in settings where specialists aren’t present. Emergency rooms, urgent cares, and even some primary care clinics don’t always have the tools or training to spot this interaction.Thankfully, things are changing. The Parkinson’s Foundation trained over 1,200 providers in 2023, cutting inappropriate prescriptions by 55% in their network. New drugs like aprepitant (Emend), which blocks a different pathway entirely, are showing 92% effectiveness without touching dopamine. A $1.2 million research grant from the Michael J. Fox Foundation is now funding a new drug designed specifically to treat Parkinson’s-related nausea without crossing into the brain.

But until those new options are widely available, vigilance is your best defense. The right antiemetic can make life more comfortable. The wrong one can send you backward-sometimes for weeks.

Can metoclopramide make Parkinson’s symptoms worse?

Yes, metoclopramide can significantly worsen Parkinson’s symptoms. It crosses the blood-brain barrier and blocks dopamine D2 receptors in the basal ganglia, which are already low in dopamine due to the disease. Studies and patient reports confirm it can trigger severe tremors, rigidity, freezing episodes, and prolonged "off" periods. The American Parkinson Disease Association lists it as a medication to avoid. Risk is estimated at 95%.

Is domperidone safe for Parkinson’s patients?

Yes, domperidone is generally considered the safest antiemetic for Parkinson’s patients. It doesn’t cross the blood-brain barrier significantly due to P-glycoprotein efflux, so it blocks nausea-causing dopamine receptors in the gut without affecting the brain. Clinical data shows less than 2% risk of worsening motor symptoms. It’s widely used outside the U.S., though in the U.S., it’s only available through a special FDA investigational program due to rare cardiac risks at high doses.

What antiemetics should Parkinson’s patients avoid?

Parkinson’s patients should avoid all dopamine D2 receptor antagonists, including: metoclopramide (Reglan), prochlorperazine (Stemetil), haloperidol (Haldol), chlorpromazine, droperidol, and promethazine. These drugs directly interfere with dopamine pathways in the brain and can cause acute worsening of tremors, slowness, and rigidity. The American Parkinson Disease Association explicitly lists these as medications to avoid.

Why isn’t domperidone available over the counter in the U.S.?

The FDA has not approved domperidone for general use in the U.S. because of rare but serious risks of heart rhythm abnormalities (QT prolongation) at high doses. However, it is available through an investigational new drug (IND) application, which most neurologists can obtain for Parkinson’s patients. Many patients get it through international pharmacies with a prescription. The safety profile at standard anti-nausea doses (10 mg 3-4 times daily) is excellent for Parkinson’s patients.

What should I do if I was given a dangerous antiemetic in the ER?

If you received metoclopramide, prochlorperazine, or another dopamine blocker and notice worsening tremors, stiffness, or difficulty moving, contact your neurologist immediately. Do not increase your levodopa dose on your own-this can cause other complications. In most cases, symptoms begin to improve within 24-72 hours after stopping the drug, but full recovery can take up to three weeks. Document the incident and report it to your pharmacy and provider to prevent future errors.

Are there non-drug ways to manage nausea in Parkinson’s?

Yes. Many patients find relief with simple lifestyle changes: eating smaller, more frequent meals; avoiding greasy or spicy foods; staying well-hydrated; and taking 1 gram of ginger daily (as capsules or tea). Some report benefit from acupressure wristbands. These approaches are safe, have no drug interactions, and are recommended as first-line by experts like Dr. Alberto Espay before turning to medication.

I've been managing my husband's Parkinson's for 8 years, and I can't believe how often ER staff hand out metoclopramide like candy. We had to go to three different hospitals before one nurse actually asked if he had Parkinson's. I carry the APDA card, but half the time they just glance at it and say 'oh, we'll be fine.' We're not fine. We're one bad prescription away from a week of not being able to walk.

OMG YES!! I literally cried when I found out domperidone was a thing!! My dad went from barely able to stand to full mobility in 48 hours after switching!! I’m so glad someone finally wrote this!! 😭🙏

It’s wild how medicine still operates like a game of telephone. You’ve got a neurologist who knows the risks, a pharmacist who reads the label, and then the ER doc who’s just trying to shut down a vomiting patient like it’s a fire alarm. No one’s talking to each other. The system’s broken. And domperidone? It’s not even a mystery drug-it’s just a victim of bureaucracy and fear of lawsuits. We’re treating nausea like it’s a war, not a symptom.

Wait-so you’re telling me Big Pharma doesn’t want domperidone approved because it’s cheap, generic, and works? And the FDA is playing along? This isn’t about heart risks-it’s about profit. They’d rather keep you on $500 Zofran pills than let you have $5 domperidone. Wake up. The real danger isn’t the drug-it’s the industry that blocks it. They’re selling fear. And we’re buying it.

Think about it: dopamine isn’t just about movement. It’s about joy. About motivation. About feeling like you’re still here. When they block it-even accidentally-they’re not just making you stiff. They’re making you numb. And the worst part? No one notices until you stop smiling. Until you stop trying. Until you become a ghost in your own body. Is that really the trade-off for a little nausea?

Let’s be real-this whole thing is a tragedy dressed up as a medical guideline. We’ve got patients in wheelchairs because a nurse didn’t read a 2-line warning. Meanwhile, in Canada, people are sipping ginger tea and taking domperidone like it’s a vitamin. The U.S. healthcare system doesn’t fail its patients-it just forgets them. And then pretends it didn’t notice.

I’m so glad this was written. My mom was given prochlorperazine last year and spent three weeks barely able to speak. She’s recovering, but it took months. Please, if you’re reading this and you have Parkinson’s-or love someone who does-print this out. Tape it to your fridge. Give it to your doctor. Don’t wait for a crisis. Prevention is the only real treatment here.

Oh my god, I just had to take my sister to the ER last week because she got sick after dinner-she’s got Parkinson’s, too-and they gave her metoclopramide… I didn’t even know it was dangerous until I read this. I sat there holding her hand while she trembled and cried, and all I could think was: why didn’t anyone tell us? Why is this not common knowledge? I feel like I failed her. I should’ve known. I should’ve fought harder. I’m so sorry, sis.

Domperidone? In the U.S.? That’s just a British fix for a British problem. We’ve got Zofran, we’ve got Emend, we’ve got cutting-edge science. Why are we letting Europe dictate our medicine? If the FDA says it’s risky, then it’s risky. End of story. Stop trying to smuggle foreign pills into our system like it’s some kind of rebellion.

Hold up. I’ve been on domperidone for two years. Zero side effects. My tremors? Gone. My nausea? Gone. But I had to order it from India. Yeah, I know it’s sketchy. But I’d rather take a pill from a stranger’s basement than let a hospital turn me into a statue. I’m not a patient-I’m a survivor. And I’m not apologizing for that.

Domperidone’s safety profile is well-documented in over 200 clinical studies across 15 countries. The QT prolongation risk at standard antiemetic doses (10 mg TID) is statistically negligible-lower than that of common antihistamines. The FDA’s stance is not evidence-based; it’s regulatory inertia. Neurologists routinely prescribe it off-label. The real failure is the lack of institutional coordination-not the drug.

This is why India leads in affordable neurology. We’ve been using domperidone for decades without a single major incident. Your FDA is stuck in the 1980s. Meanwhile, in Mumbai, a Parkinson’s patient gets domperidone at the local pharmacy, no prescription needed. You want progress? Stop pretending your system is perfect. It’s not. It’s broken.

My grandma used to say, 'If your medicine makes you sadder than your sickness, it’s not medicine-it’s a trap.' Ginger, small meals, hydration… these aren’t just 'alternatives.' They’re dignity. And sometimes, the bravest thing you can do is refuse the pill that’s supposed to help.

It’s funny how we treat nausea like a villain when it’s just a messenger. The real enemy is the system that doesn’t listen. I’ve seen patients get better just by having someone sit with them, ask how they feel, and say, 'Let’s try something gentler.' No drugs needed. Just presence. Maybe that’s the real antidote.

Just wanted to say thank you for writing this. My dad’s on domperidone now, and he’s walking again. I didn’t even know this was possible until I found this post. I’m sharing it with every doctor I know. You saved my family. Seriously. Thank you.