CIC vs IBS Symptom Comparison Tool

This tool helps distinguish between Chronic Idiopathic Constipation (CIC) and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) with constipation-predominant (IBS-C) by highlighting their key symptoms and overlaps.

Use the table below to compare features such as bowel frequency, stool consistency, and associated discomfort.

| Feature | Chronic Idiopathic Constipation | Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS-C) |

|---|---|---|

| Bowel Frequency | <3 times per week; often none for several days | Variable; may be less frequent than normal or alternating with diarrhea |

| Stool Consistency | Hard, lumpy (Bristol Stool Form Scale types 1–2) | May vary; often hard or lumpy, sometimes loose |

| Abdominal Pain | Less common or mild; not typically associated with defecation | Recurrent abdominal pain, often relieved by defecation |

| Feeling of Incomplete Evacuation | Common; persistent sensation even after bowel movement | Common; part of IBS-C diagnostic criteria |

| Bloating | Often present; can wax and wane | Common; may worsen with meals or stress |

| Straining During Defecation | Typical; difficulty passing stool | Also typical; often due to increased muscle tension |

| Diagnosis Criteria | Based on Rome IV criteria for constipation | Based on Rome IV criteria including abdominal pain linked to bowel changes |

Overlap: Both conditions share slow colonic transit and similar gut-brain signaling issues. They may coexist in the same individual.

Differences: IBS-C includes abdominal pain and symptom relief with defecation, whereas CIC focuses more on constipation severity and lack of pain.

Management: Dietary fiber, low-FODMAP diets, and probiotics benefit both conditions. Stress management plays a significant role in symptom control.

Ever wondered why some people who suffer from constant constipation later develop the cramping, bloating, and irregular bowel habits of IBS? The answer lies in shared gut mechanisms that blur the line between two seemingly separate diagnoses. This article unpacks the science, shows where the symptoms overlap, and gives you practical steps to manage both conditions.

Key Takeaways

- Chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) and IBS share gut‑brain signaling problems and microbiome imbalances.

- Rome IV criteria are the gold standard for diagnosing IBS, but they also help rule out pure constipation.

- Dietary fiber, low‑FODMAP foods, and targeted probiotics can improve symptoms of both disorders.

- When pain, weight loss, or sudden changes in stool shape appear, a doctor’s evaluation is essential.

- Understanding the link lets you choose treatment that tackles the root cause rather than just the symptoms.

What Is Chronic Idiopathic Constipation?

Chronic Idiopathic Constipation is a long‑lasting condition where stool moves too slowly through the colon, leading to hard, infrequent bowel movements without an identifiable cause. It affects roughly 10% of adults in the United States, and the “idiopathic” tag means tests usually don’t reveal structural problems, nerve damage, or medication side‑effects. Typical signs include:

- Fewer than three bowel movements per week

- Straining or a feeling of incomplete evacuation

- Hard, lumpy stools (Bristol Stool Form Scale types1‑2)

Because the colon is sluggish, patients often report abdominal bloating that waxes and wanes throughout the day.

What Is Irritable Bowel Syndrome?

Irritable Bowel Syndrome is a functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by recurring abdominal pain linked to changes in stool frequency or form. IBS comes in three sub‑types: IBS‑C (constipation‑predominant), IBS‑D (diarrhea‑predominant), and IBS‑M (mixed). The condition is diagnosed mainly through symptom patterns, most commonly using the Rome IV criteria which require:

- Recurrent abdominal pain on average at least one day per week in the last three months

- Associated with two or more of the following: improvement with defecation, change in stool frequency, or change in stool form

IBS affects about 12% of the global population, with a higher prevalence among women and younger adults.

Shared Gut Mechanisms: Why the Two Conditions Overlap

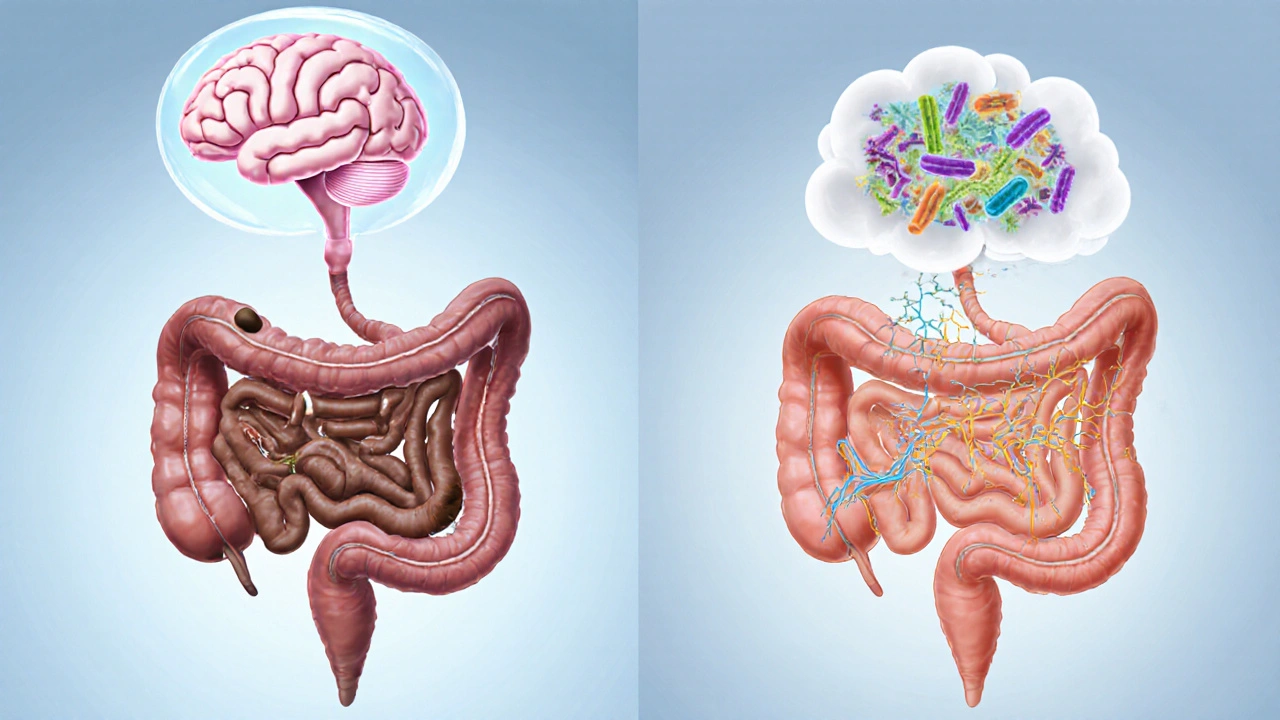

Both CIC and IBS‑C involve disruptions in the Enteric Nervous System, the “second brain” of the gut that coordinates muscle contractions. When signaling goes awry, the colon either contracts too weakly (CIC) or reacts hypersensitively to normal stretch (IBS), producing pain and irregular movements.

Research from 2023 shows that gut microbiota composition differs markedly in patients with either condition. A lower ratio of Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes and reduced short‑chain fatty acid production contribute to slower colonic transit and heightened visceral sensitivity.

Stress hormones, especially cortisol, also modulate both conditions via the gut‑brain axis. Chronic stress can blunt the motility signal, worsening constipation, while simultaneously lowering pain thresholds, a hallmark of IBS.

Symptom Comparison: CIC vs. IBS‑C

| Feature | Chronic Idiopathic Constipation | Irritable Bowel Syndrome (Constipation‑Predominant) |

|---|---|---|

| Bowel Frequency | <3 per week, often none for several days | Variable; may be <3 per week but can fluctuate |

| Abdominal Pain | Occasional, usually related to hard stool | Recurrent, cramp‑like, improves after defecation |

| Stool Form (Bristol Scale) | Types1‑2 (hard, lumpy) | Types1‑2, occasional type3 if mixed |

| Bloating | Common, mild‑moderate | Common, often severe during flare‑ups |

| Response to Fiber | Improves transit in many cases | May help or worsen symptoms depending on type |

Diagnostic Approach: When Does Constipation Become IBS?

Doctors start with a thorough history and a physical exam. Red‑flag signs-such as unexplained weight loss, anemia, or rectal bleeding-prompt colonoscopy or imaging to exclude organic disease.

If red flags are absent, the clinician applies the Rome IV criteria. A patient who meets the pain frequency rule plus at least one stool‑related criterion is classified as IBS‑C, even if they have chronic constipation.

Additional tests may include:

- Stool analysis for occult blood and infection

- Thyroid function tests (hypothyroidism can mimic constipation)

- Small‑bowel imaging or breath test for SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth)

Identifying overlapping features guides a treatment plan that tackles both motility and sensitivity.

Management Strategies That Hit Both Targets

Effective therapy blends three pillars: dietary adjustments, gut‑targeted supplements, and, when needed, prescription medication.

1. Dietary Fiber - Choose Wisely

Soluble fiber (e.g., psyllium husk) absorbs water, softening stool and promoting regularity without adding bulk that can trigger IBS pain. Insoluble fiber (wheat bran) can worsen bloating for IBS patients, so keep it limited.

Start with 5g of psyllium mixed in water once daily, gradually increasing to 10g split into two doses. Drink at least 8cups of fluid alongside.

2. Low‑FODMAP Diet

FODMAPs are fermentable carbs that feed gut bacteria, producing gas and triggering pain. A short, 4‑week low‑FODMAP trial can clarify whether specific foods intensify IBS symptoms while still allowing fiber from low‑FODMAP sources like carrots, oats, and kiwi.

3. Probiotics and Gut‑Microbiome Modulation

Probiotics containing Bifidobacterium infantis or Lactobacillus plantarum have shown modest improvements in both constipation and abdominal pain in randomized trials. Use a daily dose of 10‑12billion CFU for at least six weeks before assessing benefit.

4. Prescription Options

When lifestyle changes fall short, doctors may prescribe:

- Lubiprostone - a chloride channel activator that increases intestinal fluid, approved for CIC and IBS‑C.

- Linaclotide - a guanylate cyclase‑C agonist that speeds transit and reduces pain.

- Low‑dose tricyclic antidepressants - help lower visceral hypersensitivity, especially when pain dominates.

These agents should be used under medical supervision because they can cause diarrhea or abdominal cramps.

5. Stress Management

Since the gut‑brain axis is central to both disorders, mindfulness meditation, yoga, or regular aerobic exercise can lower cortisol and improve motility. A 30‑minute walk after meals has been shown to reduce post‑prandial bloating in IBS studies.

When to Seek Medical Help

If you notice any of the following, book an appointment promptly:

- Sudden onset of severe abdominal pain

- Unexplained weight loss or loss of appetite

- Blood in stool or black/tarry stools

- Persistent symptoms despite 8 weeks of diet and OTC measures

Early evaluation can rule out structural issues like colorectal cancer or inflammatory bowel disease, which require different treatment pathways.

Putting It All Together: A Sample 4‑Week Action Plan

- Week1: Begin a daily psyllium regimen (5g) + 2L water. Keep a symptom diary noting stool frequency, form, and pain scores.

- Week2: Add a low‑FODMAP trial; eliminate garlic, onions, wheat, and certain fruits. Continue diary.

- Week3: Introduce a probiotic (B. infantis 10BCFU). Review diary with your clinician; consider a prescription if no improvement.

- Week4: Evaluate progress. If pain persists, discuss low‑dose tricyclics or linaclotide. Maintain stress‑relief practices.

Adjust the plan based on personal tolerance; the goal is steady improvement without abrupt changes that can upset gut bacteria.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can chronic constipation turn into IBS?

Yes, especially when the underlying gut‑brain signaling remains dysfunctional. Over time, the constant stretch of a full colon can sensitize nerves, leading to the abdominal pain that defines IBS.

Is a high‑fiber diet safe for IBS‑C?

Soluble fiber like psyllium is generally safe and beneficial. Insoluble fiber can trigger bloating, so it’s best to start low and monitor symptoms.

Do probiotics actually work for constipation?

Evidence shows certain strains-not all-can improve stool frequency and reduce abdominal discomfort. Look for clinically studied strains such as Bifidobacterium infantis.

Should I get a colonoscopy if I have chronic constipation?

Only if you have red‑flag symptoms (bleeding, anemia, weight loss) or if your doctor suspects an underlying structural problem. Routine colonoscopy isn’t required for uncomplicated CIC.

What lifestyle changes help both conditions?

Regular physical activity (30minutes most days), consistent meal times, adequate hydration, stress‑reduction techniques (mindfulness, yoga), and a gradual increase in soluble fiber form the core of a dual‑benefit plan.

Reading the comparison between chronic idiopathic constipation and IBS really opened my eyes to how intertwined these conditions truly are. The article does a solid job of laying out the Rome IV criteria for both disorders and how they overlap in gut‑brain signaling. It explains that slow colonic transit is a hallmark of CIC while hypersensitivity of the enteric nervous system is central to IBS. I appreciate the detailed breakdown of stool frequency and consistency, especially the use of the Bristol Stool Form Scale as a visual aid. The emphasis on bowel frequency fewer than three times per week for CIC versus the variable pattern in IBS‑C helps clinicians differentiate the two. Moreover, the piece highlights that abdominal pain is not common in pure constipation but is a defining feature of IBS. The discussion of microbiome alterations, particularly the reduced Bacteroidetes to Firmicutes ratio, adds a layer of mechanistic insight. Stress hormones like cortisol are noted as modulators of both motility and pain thresholds, underscoring the importance of stress management. Dietary interventions such as increased fiber and low‑FODMAP diets are presented as common therapeutic avenues. Probiotic supplementation is also mentioned as beneficial for restoring short‑chain fatty acid production. The article wisely warns that sudden changes in stool shape, weight loss, or severe pain warrant immediate medical evaluation. I also like that the tool is presented as educational and not a substitute for professional diagnosis. Overall the content balances scientific rigor with practical advice, making it useful for both patients and healthcare providers. Finally, the inclusion of a symptom comparison table serves as a quick reference that can be printed out for discussions during appointments.

While the exposition admirably covers the salient aspects of CIC and IBS, one must attend to the subtle nuances that the Rome IV criteria encapsulate, particularly the temporal relationship between pain and defecation, which the author seemingly glosses over. The delineation of visceral hypersensitivity warrants a more rigorous exegesis, given its pivotal role in IBS pathophysiology. Additionally, the microbiome discourse, though present, could have benefited from citing specific taxa alterations beyond the generic Bacteroidetes‑Firmicutes ratio. It is also incumbent upon the writer to acknowledge the heterogeneity of patient responses to low‑FODMAP regimens, which, while efficacious for many, may precipitate nutritional deficiencies in a subset. The article’s assertion that stress management plays a "significant role" would be more compelling if supported by quantitative data from longitudinal studies. Lastly, the tabular representation, though informative, suffers from a lack of statistical context-such as prevalence rates-that would enhance its evidentiary weight.

Great summary! If you’re looking for quick tips, try adding a tablespoon of ground flaxseed to your breakfast cereal – it can help soften stool and add some healthy omega‑3s. Also, drinking a glass of warm water with lemon first thing in the morning can jump‑start digestion. Remember to move around after meals, even a short walk can make a difference. And if symptoms get worse, a chat with your doctor about a possible probiotic like Bifidobacterium can be worth it.

One must concede that the article approaches the subject with a certain didactic simplicity that, while accessible, betrays an underestimation of the epistemic complexities inherent in functional gastrointestinal syndromes. The reliance upon tabular dichotomies, though pedagogically convenient, inadvertently reduces a multifaceted nosology to a binary schema. Such reductionism risks obfuscating the ontological fluidity between constipation-dominant phenotypes and their protean manifestations.

Indeed, the explication of gut‑brain interplay in the piece invites contemplation of the Ayurvedic concepts of agni and dosha balance, which echo modern understandings of neural modulation of motility. It is fascinating that the authors reference short‑chain fatty acids, the very metabolites that our traditional fermented foods, such as kimchi and idli, have long harnessed to promote colonic health. Moreover, the stress‑cortisol axis, described with clinical precision, aligns with the ancient yogic principle of prana regulation through pranayama, offering a culturally integrative therapeutic avenue. The synthesis of empirical data with holistic practices could elevate the discourse beyond mere symptom charts, fostering a truly interdisciplinary approach.

Just a heads up – if you’re trying the fiber route, start slow. Too much at once can actually make bloating worse. Mix in some probiotic yogurt or kefir and see how your gut reacts. And don’t forget to stay hydrated; water helps fiber move through.

Whoa!!! This is totally a government cover‑up, right??

Interesting take, but I think the article could use more nuance. The symptoms overlap a lot, and sometimes the line between CIC and IBS‑C is practically invisible. 🤔

Awesome read! I love how it breaks down the diff between constipaton and IBS – makes it super clear for folks who aren't med students. The tips on fiber are spot on, just make sure to add enough water!

From a pathophysiological standpoint, the delineation between motility dysregulation and visceral hypersensitivity constitutes a bifurcated paradigm that necessitates a multimodal therapeutic algorithm. The article's cursory mention of low‑FODMAP diets fails to address the requisite re‑introduction phase, a critical component for long‑term compliance and microbiome resilience. Moreover, the omission of neuromodulatory agents such as 5‑HT4 agonists or centrally acting agents like gabapentin represents a lacuna in the management schema, potentially disadvantaging patients with refractory symptomatology. An integrative framework encompassing dietary modulation, pharmacologic titration, and psychobehavioral interventions would furnish a more robust, evidence‑based roadmap.

Thanks for the clear overview. It helps a lot to see the differences side by side.

Glad it was useful.

When pondering the interconnectedness of CIC and IBS, one cannot escape the philosophical musings on the self‑referential nature of the gut-brain axis. It's as if the intestines whisper secret codes to the brain, and the brain, in turn, replies with nuanced commands that shape our very perception of comfort. This dialogue, mediated by neurotransmitters and microbial metabolites, suggests that the boundaries we draw between "physical" and "psychological" ailments are, perhaps, more porous than we imagine. Embracing this holistic view may inspire clinicians to blend dietary guidance, stress‑reduction techniques, and targeted pharmacology into a symphony that honors the complexity of human physiology.