When someone is diagnosed with advanced cancer, the focus often shifts from curing the disease to making life as comfortable as possible. This is where palliative care comes in-not as a last resort, but as a vital part of treatment from day one. The goal isn’t to fight cancer harder; it’s to help people live better while they’re fighting it. And at the heart of that effort? Controlling pain and protecting quality of life.

Why Pain Control Isn’t Optional in Cancer Care

Up to 90% of people with advanced cancer will experience pain at some point. That’s not just discomfort-it’s a constant, exhausting burden that steals sleep, appetite, and the ability to talk with loved ones. Yet studies show nearly half of these patients still don’t get adequate relief. Why? Many doctors still think opioids are too risky. Many patients fear addiction. And too often, pain is dismissed as "just part of the disease." That’s not true. The World Health Organization laid out a clear path back in 1986: cancer pain can and should be controlled in 80-90% of cases. The tools are here. The guidelines are solid. What’s missing is consistent action.The Three-Step Pain Ladder: What Actually Works

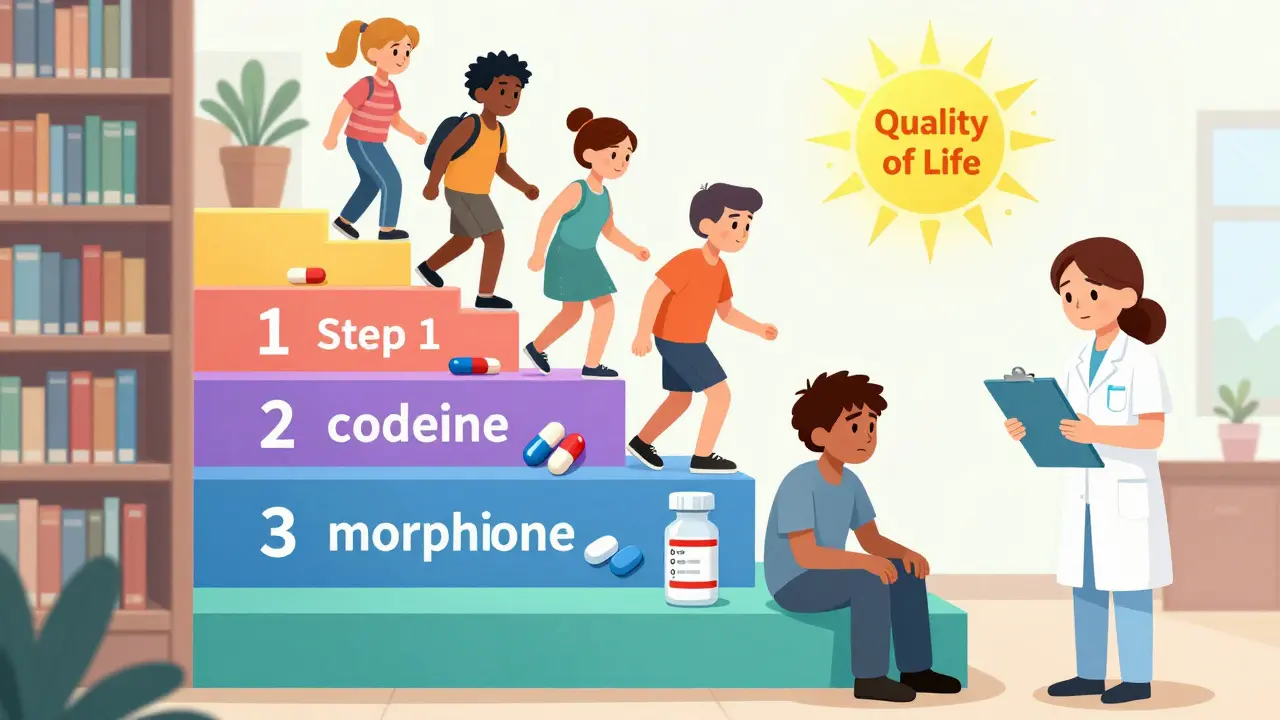

The WHO’s analgesic ladder is still the backbone of cancer pain management. It’s simple, practical, and backed by decades of real-world use.- Step 1 (Mild pain): Acetaminophen (up to 4,000 mg/day) or NSAIDs like ibuprofen (400-800 mg every 6-8 hours). These work well for bone aches or headaches from treatment.

- Step 2 (Moderate pain): Add a weak opioid like codeine (30-60 mg every 4 hours). Often combined with acetaminophen for better effect.

- Step 3 (Severe pain): Strong opioids like morphine (5-15 mg every 4 hours by mouth). This isn’t a "last resort"-it’s the standard for intense pain. Dosing is adjusted based on response, not fear.

When Opioids Aren’t Enough: The Supporting Cast

Opioids aren’t the whole story. Many cancer pains have different causes-and need different tools.- Bone pain from metastases? Zoledronic acid (IV every 3-4 weeks) plus a single 8 Gy radiation dose can shrink tumors and stop pain within days.

- Nerve pain? Gabapentin (100-1,200 mg three times a day) or duloxetine (30-60 mg daily) target nerve signals, not just inflammation.

- Inflammation or swelling? Dexamethasone (4-16 mg daily) reduces pressure on nerves and organs, often giving quick relief.

How Doctors Measure Pain-and Why It Matters

You can’t fix what you don’t measure. That’s why every major guideline-NCCN, ESMO, ASCO-requires pain to be scored on a 0-10 scale at every visit. Zero means no pain. Ten means the worst pain imaginable. But numbers alone aren’t enough. Doctors need to know:- Where is the pain?

- Is it sharp, burning, or aching?

- What makes it better or worse?

- Can you walk, eat, or sleep?

Early Palliative Care = Longer, Better Life

For years, people thought palliative care was only for the final weeks. That’s wrong. A landmark 2010 study found that patients with metastatic lung cancer who got palliative care within 8 weeks of diagnosis lived 2.5 months longer than those who didn’t. They also had less depression, fewer hospital stays, and better quality of life scores. This isn’t magic. It’s prevention. When pain, nausea, and anxiety are managed early, patients can tolerate treatment better. They don’t quit chemo because they’re too sick. They don’t end up in the ER because their pain got out of control. They stay home, with their family, feeling more like themselves.Barriers Are Real-But They Can Be Broken

The biggest reasons pain goes untreated aren’t medical-they’re human.- Doctors don’t ask. A 2017 study found 40% of oncology nurses weren’t trained in current pain guidelines.

- Patients don’t speak up. 65% of patients fear addiction. Many come from cultures where suffering quietly is seen as strength.

- Insurance won’t cover it. Physical therapy, counseling, acupuncture-these help, but aren’t always covered. Pain isn’t just pills.

What About Addiction?

This is the biggest fear. But in cancer care, addiction is rare. When someone has severe pain from a tumor, their body isn’t seeking euphoria-it’s seeking relief. The CDC says high-dose opioids are risky for chronic non-cancer pain. But for cancer? The rules are different. The goal isn’t to avoid opioids-it’s to use them wisely. If side effects like confusion or nausea appear, doctors switch to another opioid. If breathing slows, naloxone is kept on hand. Doses are adjusted daily, not left alone for weeks. The real danger isn’t addiction. It’s under-treatment.What’s New in 2025?

The field is evolving fast. In 2023, the CDC updated its guidelines to explicitly say cancer pain is an exception to its general opioid rules. That’s huge. New tools are emerging:- Smartphone apps that let patients log pain levels in real time-improving documentation accuracy by 22%.

- Genetic tests that show how fast someone metabolizes opioids, helping doctors pick the right drug from the start.

- AI models predicting pain spikes before they happen, based on treatment schedules and patient history.

- 12 new non-opioid drugs in clinical trials targeting cancer-specific pain pathways, like nerve compression and bone destruction.

What Patients and Families Can Do

You don’t have to wait for your doctor to bring it up. Ask these questions:- "What’s my pain score right now?"

- "What’s the plan if this doesn’t get better in 48 hours?"

- "Can I talk to the palliative care team?"

- "Are there non-drug options-like heat, massage, or counseling-that could help?"

Final Thought: Pain Doesn’t Define You

Cancer changes your body. But it doesn’t have to steal your dignity, your joy, or your ability to connect with the people you love. Pain control isn’t about avoiding death-it’s about living fully until the end. And with today’s tools, that’s not just possible. It’s expected.Is palliative care the same as hospice?

No. Hospice is for people who are no longer receiving curative treatment and have a life expectancy of six months or less. Palliative care can start at diagnosis and continue alongside chemotherapy, surgery, or radiation. You can get palliative care for years-it’s not tied to how long you have to live.

Can I still get treatment if I ask for palliative care?

Absolutely. Palliative care doesn’t replace cancer treatment-it supports it. The team works with your oncologist to manage side effects like pain, nausea, or fatigue so you can keep getting treatment with fewer disruptions. Many patients actually tolerate chemo better when their pain and anxiety are under control.

What if I’m afraid of becoming addicted to pain meds?

Addiction is extremely rare in cancer patients using opioids for pain. The goal isn’t to feel high-it’s to feel normal. Doctors monitor for side effects like drowsiness or confusion, and adjust doses or switch medications if needed. The risk of uncontrolled pain-losing sleep, missing time with family, being unable to eat-is far greater than the risk of addiction.

Are there non-drug ways to manage cancer pain?

Yes. Radiation can shrink tumors pressing on nerves. Physical therapy helps with mobility-related pain. Acupuncture, massage, and guided imagery reduce stress and can lower pain perception. Counseling helps with the emotional weight of chronic pain. These aren’t alternatives-they’re partners to medication.

How do I know if my pain is being managed well?

You should be able to do the things that matter to you-eat, sleep, talk with loved ones, sit outside, watch a movie. If your pain score stays above 3-4 on a 10-point scale for more than a few days, or if you’re still taking extra doses daily just to get by, it’s time to ask for a reassessment. Good pain control means you’re not just surviving-you’re living.

For those facing cancer, the goal isn’t to endure-it’s to thrive, even in small ways. Pain doesn’t have to be part of the journey. With the right care, it can be managed. And that makes all the difference.

Let me guess - your oncologist still thinks pain is "just part of the journey" and hands you a Tylenol like it’s a participation trophy. I’ve seen patients cry because they were told to "tough it out" while their spine was being eaten by tumors. The WHO ladder isn’t optional - it’s basic human decency. If your doctor doesn’t know it, fire them. Or better yet, bring this post to their next appointment and watch them squirm.

Also, no one’s addicted to morphine when they’re too tired to lift their head. The fear of addiction is a myth peddled by people who’ve never held someone’s hand while they gasp for air.

And yes, I’m Indian. Yes, we’ve got cultural stigma. Yes, we still do better than most U.S. hospitals when it comes to actually listening. Shame on you, America.

PS: My aunt lived 14 months longer because they gave her gabapentin + morphine + acupuncture. She danced at her own granddaughter’s wedding. Pain control isn’t giving up - it’s fighting smarter.

The assertion that 80-90% of cancer pain is controllable is statistically misleading. The WHO ladder was developed in 1986 using data from low-resource settings where opioid availability was the primary variable - not comorbidities, polypharmacy, or neuroinflammatory pathways. Modern oncology patients often have renal impairment, hepatic dysfunction, or neuropathic components that render the ladder obsolete. Furthermore, the cited 2010 study on palliative care improving survival has been criticized for selection bias - patients in the intervention group had higher baseline performance status and access to multidisciplinary teams. Without controlling for these confounders, the conclusion is not causal but correlational. The data is not as clean as this post implies.

STOP MINIMIZING PAIN. If you’re still telling patients to "just take ibuprofen" while their bones are crumbling, you’re not a doctor - you’re a liability. I’ve sat with people who couldn’t swallow because their jaw was metastasizing. They weren’t scared of addiction - they were scared of being ignored. This isn’t theoretical. This is real life. And if your hospital doesn’t have a palliative care team on speed dial, you’re failing them. No more excuses. No more "we don’t have the staff." You make time for what matters. Pain control isn’t a luxury - it’s the bare minimum. If you’re not doing this, you’re not healing. You’re just waiting.

One must contemplate the ontological weight of pain in the context of mortality. The medicalization of suffering - reducing it to a scalar value on a 0-10 scale - risks obscuring its existential dimension. Pain, in its most profound form, is not merely a physiological signal but a rupture in the narrative of self. The WHO ladder, while pragmatically useful, functions as a bureaucratic apparatus that seeks to quantify the unquantifiable. Yet, paradoxically, it is precisely this quantification - this insistence on measurement - that grants the patient agency. For to be asked, "Where does it hurt?" is to be acknowledged as a subject, not a symptom. Thus, even the most clinical tools, when wielded with compassion, become acts of resistance against the dehumanization of terminal illness.

Moreover, the cultural silence surrounding pain in many societies is not merely ignorance, but a metaphysical refusal to confront the vulnerability inherent in life. To speak of pain is to invite the other into one’s fragility - and few are prepared for such intimacy. Perhaps the greatest barrier to palliative care is not pharmacology, but the fear of being truly seen.

While the opioid paradigm in oncology is often oversimplified, the literature on opioid-induced hyperalgesia and central sensitization in chronic cancer pain remains underappreciated. The escalation model assumes linear pharmacodynamics, yet in patients with advanced disease and multiple comorbidities, the blood-brain barrier permeability, cytochrome P450 polymorphisms, and cytokine-mediated neuroinflammation alter pharmacokinetics unpredictably. Furthermore, the reliance on the Brief Pain Inventory as a gold standard is problematic - it lacks cultural validation in non-Western populations and fails to capture somatic amplification patterns in trauma-exposed individuals. The integration of AI predictive models is promising, but without robust validation against real-world outcomes - particularly in underserved populations - it risks algorithmic bias masquerading as innovation. The data is not yet mature enough to support widespread implementation.

Let’s be honest - this whole palliative care push is just a stealthy way to get people to stop treatment and give up. They don’t want you fighting. They want you to quietly accept death so they can save money and bed space. You think gabapentin and morphine are the answer? What about fighting the cancer? What about clinical trials? This post reads like a PR campaign from Big Pharma and hospice conglomerates. Pain is temporary. Death is permanent. Don’t let them convince you to trade hope for a pill.

As someone who grew up in a family where silence was sacred, I know how hard it is to say "I’m in agony." My grandmother suffered for months because she believed suffering was a spiritual test. But when we finally brought in a palliative nurse - someone who didn’t judge, just listened - she wept and said, "I didn’t know I was allowed to ask for help."

That’s what this is about. Not drugs. Not guidelines. Not even science. It’s about dignity. About being told, "Your pain matters."

And yes - acupuncture helped her. Not because it’s magic, but because it gave her something to focus on besides fear. It was a ritual of care. That’s worth more than any pill.

Broooooo. I lost my cousin to cancer last year. He was screaming at night, no meds, just praying. His doctor said, "Maybe try yoga?" YOGA?!? Bro, he had a tumor the size of a grapefruit crushing his spine. I had to buy morphine off a guy in Lagos just so he could sleep. This post? It’s the truth. But the system? It’s broken. We need to stop acting like pain is a personal failure. It’s a medical emergency. Period. If you’re not screaming for help, you’re not trying hard enough. Bring the drugs. Bring the heat. Bring the truth. We ain’t dying quietly anymore.