ADRs Classification Quiz

Test Your Knowledge

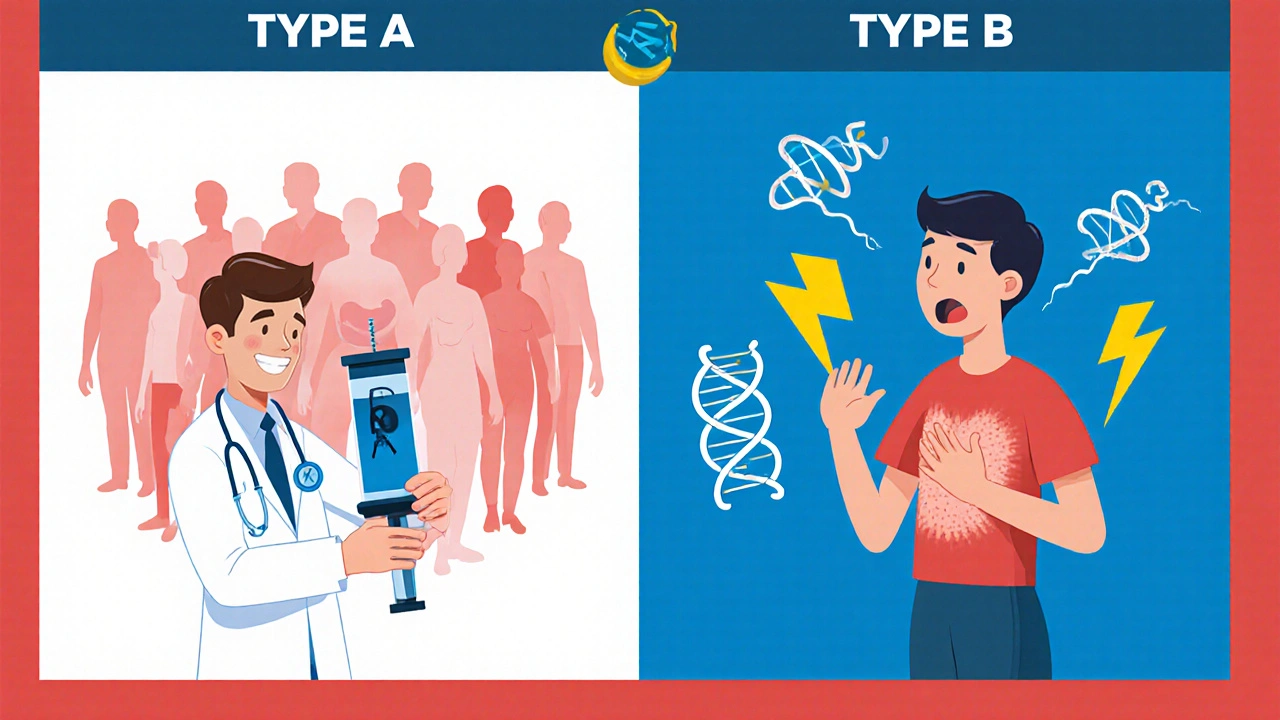

This quiz tests your understanding of predictable (Type A) vs. unpredictable (Type B) adverse drug reactions. Select the best answer for each question.

What is the key characteristic that distinguishes Type A (predictable) reactions from Type B (unpredictable) reactions?

Which of the following statements about Type A reactions is most accurate?

Which of these is most likely to be a Type B (unpredictable) adverse drug reaction?

What percentage of all adverse drug reactions are Type A (predictable) reactions?

Which approach is most effective for preventing Type B (unpredictable) adverse drug reactions?

When you hear “side effect,” you probably picture a headache or upset stomach. In reality, Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are harmful or unintended responses that occur while taking a medication at normal doses. Understanding whether an ADR is predictable or unpredictable can be the difference between a quick fix and a life‑threatening emergency.

What makes a side effect predictable?

Predictable reactions, known in the classification as Type A reaction, follow the drug’s primary pharmacology. They tend to be dose‑dependent, show up in many patients, and usually reverse when you lower the dose or stop the drug.

- Mechanism is well‑understood (e.g., NSAIDs block prostaglandin production, which can erode the stomach lining).

- Incidence rates hover around 75‑80 % of all ADRs.

- Common examples: gastrointestinal bleeding from NSAIDs, hypotension from antihypertensives, sedation from opioids.

Because the link between dose and effect is clear, clinicians can often prevent Type A reactions by adjusting the prescription or monitoring lab values.

What makes a side effect unpredictable?

Unpredictable reactions, or Type B reaction, do not follow the drug’s expected pharmacology. They are rare, not dose‑related, and arise from individual susceptibility-often genetic or immune‑mediated.

- Mechanism is poorly understood; less than a quarter of Type B reactions have a clear pathway.

- They account for roughly 20‑25 % of all ADRs but cause a disproportionate share of severe outcomes.

- Typical cases: Stevens‑Johnson syndrome after sulfonamides, anaphylaxis from penicillin, hemolysis in G6PD‑deficient patients.

Because you can’t predict the dose needed to trigger a Type B reaction, prevention leans heavily on genetic screening, patient history, and vigilant monitoring.

Side‑effect showdown: Type A vs. Type B

| Aspect | Type A (Predictable) | Type B (Unpredictable) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Directly linked to drug’s known pharmacology | Often immune‑mediated or genetic; unrelated to primary action |

| Dose‑dependency | Yes - higher dose → higher risk | No - occurs at therapeutic doses |

| Incidence | 75‑80 % of ADRs | 20‑25 % of ADRs |

| Mortality risk | Low (≈1 % of serious cases) | High (≈15‑20 % of serious hospitalizations) |

| Preventability | ~70 % with dose adjustment | <10 % without genetic testing |

| Typical examples | NSAID‑induced GI bleed, opioid‑induced sedation | Stevens‑Johnson syndrome, drug‑induced hemolysis |

Why the distinction matters for drug safety

Numbers tell a clear story. The World Health Organization reported 5‑10 Type A ADRs per 100 hospital admissions, whereas Type B ADRs appear in 1‑2 per 100 admissions but claim a larger share of deaths. In the United States, ADRs cause over 770,000 injuries and deaths each year-most of those fatal cases stem from Type B reactions.

Financially, the burden is huge: annual U.S. spending on ADR management tops $30 billion. Predictable reactions soak up about $22.6 billion, while unpredictable ones, though less frequent, gobble $7.5 billion because treatment often requires intensive care, prolonged hospitalization, or even litigation.

Managing predictable reactions: a practical toolkit

- Baseline assessment - Check renal and hepatic function before starting drugs known for dose‑related toxicity (e.g., NSAIDs, ACE inhibitors).

- Therapeutic drug monitoring - Use plasma level checks for narrow‑window drugs like digoxin or lithium.

- Step‑wise dose titration - Start low, go slow. Incremental increases let you spot the dose‑response curve early.

- Patient education - Teach patients to watch for early signs (e.g., dark stools for GI bleed) and to report them immediately.

- Electronic decision support - Integrate alerts for high‑risk combinations into the EHR; studies show this cuts assessment time from 15-20 minutes to under 10 minutes.

These steps target the 70 % of Type A ADRs that are preventable with proper monitoring.

Spotting and preventing unpredictable reactions

Because you can’t rely on dose, you need a different playbook.

- Genetic screening - Test for HLA‑B*1502 before prescribing carbamazepine to patients of Asian ancestry; the same principle applies to HLA‑B*5701 for abacavir.

- Pharmacogenomic testing - Use panels that include CYP2C9, VKORC1, and TPMT; the FDA now requires these for certain anticoagulants and thiopurines.

- Allergy history - Document any prior drug eruptions, even if mild; up to 63 % of clinicians say penicillin allergy is their top Type B concern.

- Monitoring for early immune signals - Check eosinophil count or skin rash within the first week of high‑risk drugs.

- Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) - Follow FDA‑mandated REMS for drugs with known severe Type B risk; 64 active REMS programs focus on this category.

While only about 30 % of severe Type B reactions are currently predictable with existing genetic tests, the proportion is rising as more HLA‑drug links are discovered.

Future directions: AI, big data, and precision medicine

Artificial intelligence is already reshaping prediction. A 2022 pilot using 10 million electronic health records achieved 89 % accuracy for Type A ADRs but only 47 % for Type B. The gap highlights the complexity of gene‑environment interactions that drive unpredictable reactions.

Large‑scale initiatives like NIH’s All of Us program are adding new HLA‑drug associations every year, expanding the toolkit for pre‑emptive testing. By 2030, the International Serious Adverse Events Consortium aims to cut severe Type B events by half through widespread genomic screening.

Meanwhile, the pharmacovigilance market is booming, projected to double by 2027. More hospitals are embedding clinical decision support that flags potential Type B risks at the point of prescribing, shortening the time to recognize a problem.

Quick checklist for clinicians

- Identify whether the drug’s known side effects fall into Type A or Type B.

- For Type A, verify baseline labs, use dose‑adjustment protocols, and set up monitoring labs.

- For Type B, review allergy history, order relevant genetic panels, and educate patients on warning signs.

- Leverage EHR alerts for high‑risk drug‑drug interactions.

- Document any ADR thoroughly in MedWatch or your institution’s reporting system.

Following this list can dramatically improve patient outcomes and reduce costly hospital stays.

What is the main difference between Type A and Type B side effects?

Type A reactions are dose‑related, predictable, and stem from a drug’s known mechanism. Type B reactions are rare, not dose‑related, and often involve immune or genetic factors.

How common are predictable side effects?

About 75‑80 % of all adverse drug reactions are Type A, making them the most frequent category.

Can genetic testing prevent unpredictable reactions?

Yes, for certain drugs. Testing for HLA‑B*1502 before carbamazepine or HLA‑B*5701 before abacavir can avoid severe Stevens‑Johnson syndrome or hypersensitivity.

What role does the FDA’s MedWatch program play?

MedWatch collects voluntary reports of ADRs, helping regulators spot safety signals. However, only 42 % of serious ADRs are correctly classified when first reported.

Are there cost differences between managing Type A and Type B reactions?

Yes. Predictable reactions consume about $22.6 billion annually, while unpredictable ones, though fewer, cost roughly $7.5 billion because they often need intensive care and longer stays.

Wow, the distinction between Type A and Type B ADRs is crystal‑clear, isn’t it?; predictable reactions follow the drug’s primary pharmacology, they’re dose‑dependent, and they pop up in a large chunk of patients-think 75‑80 % of all adverse events-so you can often dodge them by tweaking the dose, monitoring labs, or simply swapping meds, right?; unpredictable reactions, on the other hand, are the rogue elements, not tied to dosage, often immune‑mediated or genetic, and while they only make up about 20‑25 % of ADRs, they pack a far heavier punch in terms of severity, hospitalization, and mortality; that’s why genetic screening and a thorough patient history are non‑negotiable, especially for high‑risk drugs like sulfonamides or penicillins.

Honestly, when I read that table I felt like I was watching a medical drama unfold-type B reactions are the plot twists nobody saw coming, and the stakes are sooo high! The whole thing is definitely a reminder that we can’t just rely on dosage charts; we need to listen to the patient’s story, even if they’re “just a rash” that could defiantly turn into Stevens‑Johnson. It’s like the body is playing a cruel game of hide‑and‑seek, and we’re left trying to recieve every clue before it’s too late.

Great breakdown! It’s encouraging to see how much we can actually prevent just by paying attention to dose adjustments for Type A reactions-most of those are manageable with a simple titration. For Type B, I’d say the key is proactive screening; pharmacogenomics is becoming more accessible, and catching a G6PD deficiency before prescribing certain antimalarials can save lives. Bottom line: knowledge plus vigilance equals safety.

Meh.

Oh, absolutely, because “just titrate a dose” solves everything, right? In the real world we’re drowning in polypharmacy, drug‑drug interactions, and those pesky “off‑label” uses that turn a simple analgesic into a liability nightmare. Let’s not forget the “n‑of‑1 trials” we conduct on the fly when the EMR flags a potential Type B event-yeah, that’s the glamorous side of pharmacovigilance, where we speak in acronyms and hope the FDA won’t bite.

Predictable side effects are manageable; unpredictable ones are not.

That’s a solid summary, but remember it’s also a team effort-pharmacists, nurses, and patients all play a role in spotting those rare reactions early, so everyone’s voice matters in the safety conversation.

Listen, the whole predictable vs. unpredictable side‑effect debate is more nuanced than most people admit, and that’s why I often push back on the simplistic “dose‑adjustment solves everything” narrative. First, the pharmacokinetic models we rely on for Type A reactions are based on population averages, which don’t always translate to the individual patient sitting in front of you, especially when comorbidities alter metabolism. Second, while genetic screening sounds like a silver bullet, the allele frequencies for many adverse‑reaction markers are still low, and the cost‑benefit ratio can be questionable in routine practice. Third, let’s not overlook the role of environmental factors-diet, concomitant herbal supplements, and even smoking status can shift the risk profile dramatically, making a supposedly “predictable” reaction behave oddly. Fourth, the regulatory landscape pushes manufacturers to label every conceivable adverse event, which inflates the perceived frequency of Type B reactions and can lead to alarm fatigue among clinicians. Fifth, the placebo‑nocebo effect can masquerade as a side effect, blurring the line between pharmacologically driven and psychosomatic symptoms. Sixth, clinicians often miss the early warning signs because electronic health records flag alerts by severity but not by subtlety, and a low‑grade rash might get buried under a cascade of higher‑priority notifications. Seventh, the literature is riddled with case reports of “idiosyncratic” reactions that later turn out to have mechanistic explanations once new pathways are discovered, so today’s Type B could be tomorrow’s Type A. Eighth, the patient’s own narrative-how they describe symptoms, timing, and context-remains the most valuable data point, yet it’s frequently under‑documented. Ninth, I’ve seen cases where aggressive dose reduction for a predictable reaction led to sub‑therapeutic efficacy, causing disease flare‑ups that were more dangerous than the original side effect. Tenth, the culture of “more testing = better safety” can paradoxically increase risk by exposing patients to invasive procedures that carry their own complications. Eleventh, consider drug–drug interactions that convert a benign pharmacological effect into a toxic one, a scenario that doesn’t fit neatly into the Type A/Type B box. Twelfth, the pharmacoeconomic implications of extensive screening programs can divert resources from other essential services, creating a different kind of systemic risk. Thirteenth, many clinicians are still trained under the old dichotomy and may under‑appreciate emerging biomarkers that predict rare reactions. Fourteenth, the legal environment pushes for defensive prescribing, which can result in over‑cautious avoidance of certain drug classes, ultimately limiting therapeutic options for patients who could have benefited. Finally, the bottom line is that drug safety is a dynamic interplay of biology, technology, economics, and human factors, and reducing it to a simple predictable/unpredictable rubric does a disservice to the complexity of real‑world medicine.